Archive for October 2011

The Potential of Personalized Advertising in Tablet/eReading Context

Due to decreased effectiveness of traditional mass advertising (i.e. messages produced in identical messages for a non-specific audience) and increase in new communication technologies (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a), Internet’s popularity, and personal information databases (M2PressWIRE, 2006; Marketing News, 2006; Trollinger, 2006), different one-to-one marketing (Friedman and Vincent, 2005), database marketing (Wehmeyer, 2005) and relationship marketing (Palmatier et al., 2006) methods have been gaining ground. Indeed, not only have budgets for personalized advertising been increasing but also diverse types of personalized advertising have been proliferating (Yuan and Tsao, 2003). This diversity in the type and amount of personalized advertising (Pramataris et al., 2001) manifests itself in online consumption in the form of website cookies, personalized interactive advertising, and smart banners (Yuan and Tsao, 2003). Since tablets and eReading devices have several similarities with personal computers and, hereby, online advertising, it is presumable that the utilization of personalized advertising will find its way to the tablet/eReading medium.

Definition

Personalized advertising is “designed to convey a customized message at the right time to the right person using diverse, advanced media” (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a, p. 503) with the help of personal information about consumers (Hyunjae & Cude 2009b). It is advertising that is created for a consumer using information about the consumer (Yuan and Tsao, 2003; Wolin and Korgaonkar, 2005). It differs from somewhat similar concepts, such as customized advertising (Tsang et al., 2004; Gal-Or and Gal-Or, 2005) and interactive advertising (Sasser et al., 2007) in the sense that the message can be delivered via any type of media (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a).

Benefits

There are several benefits associated with personalized advertising that speak for its use in marketing. First of all, personalized advertising may be more effective because messages are individualized (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000); personalized advertising can increase user involvement and, hence, advertisement’s effectiveness (Stewart and Ward, 1994; Roehm and Haugtvedt, 1999; Pavlou and Stewart, 2000; Yuan and Tsao, 2003; O’Leary et al., 2004). As consumers receive only messages that are relevant to them (e.g. referring to users by name and mentioning consumers’ specific interests in an advertisement) (Rodgers and Thorson 2000), personalized advertising can generate purchase intentions or other desired responses (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000). Consumers’ greater involvement (i.e. increased clicking activity) (Nowak et al. 1999), in turn, may increase overall satisfaction with advertising (McKeen et al. (1994) and advertising effectiveness (Howard and Kerin 2004). Indeed, advertising effectiveness is affected by the degree to which advertising is perceived personalized and individually focused (Pavlou and Stewart 2000).

The above-mentioned benefits are remarkably relevant for the highly interactive tablet/eReading medium where it is technically possible to collect personal information about users. Since e-commerce is strongly present in the tablet/eReading context commerce (cf. Forrester Research; Miller 2011), personalized advertising may offer distinctive benefits for call-to-action advertising. In other words, consumers are not only exposed to more relevant advertising but they may also purchase these custom offered goods through the same medium right away.

Drawbacks

Personalized advertising entails certain drawbacks too. Consumers may, for instance, reject personalized advertising due to increased privacy concerns (Sheehan and Hoy, 1999; Tsang, Ho, and Liang, 2004; Miyazaki and Fernandez, 2000; Sacirbey, 2000; Phelps et al., 2001); they may experience negativity, when they have not allowed it in the first place (Tsang et al. 2004). These feelings of privacy invasion (i.e. abuse of consumer information in databases) (Caudill and Murphy, 2000) are to decrease advertising effectiveness (Sheehan, 1999; Gurau et al., 2003).

Secondly, as advertisers and consumers become more sophisticated, both parties expect personalized advertising ever more (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a). Consumers, in particular, urge increasingly individualized attention, one-to-one communication and personalized offers (Gurau et al. 2003), which can become very burdensome.

Finally, research results suggest that consumers are very unlikely to take personalized advertising seriously if it is delivered online; they are not very interested in the advertised products, their purchase intentions are low, and they are unlikely to recommend advertised products (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a). However, personalized ads on the pages of electronic newspapers or magazines may yield different results.

Conclusion

Personalized advertising entails both benefits and drawbacks. As some researchers argue that consumers are likely to experience negative perceptions of personalized advertising, regardless of delivery channel (Hyunjae and Cude 2009a;b), it is recommended that marketers who utilize personalized advertising acknowledge its possible negative effects (e.g. Nowak et al., 1999; Sacirbey, 2000). In particular, marketers ought not to send personalized advertising messages to potential customers without prior permission (Tsang et al. 2004) nor use online personalized advertising as such but rather in a balanced combination with traditional personalized advertising (Trollinger, 2006; Hyunjae & Cude 2009a;b). Eventually, it is essential to understand consumers’ perceptions of personalized advertising (Hyunjae & Cude 2009a). In particular, in terms of tablet/eReading context it essential to acknowledge that tablet and eReading device manufacturers can restrict the amount of user information they give away. Hence, user “personification” may not be as effective as it could be in a situation where the media “owners” have full access to customer data.

Advertising Types in eReading/Tablet Context – Free Ad-Funded Content

A vast majority of publishing content – magazines and newspapers – in eReading and tablet medium operate on a pay basis. That is, even though most of eReading/tablet magazines and newspapers have advertisements within, the magazine or newspaper costs still for end customers. In these cases, the revenue model is congruent with the traditional print version where both advertising revenue and customer payments are utilized. In addition to this ‘traditional’, dualistic revenue model, publishers may also count on fully ad-funded content and, therefore, offer content to their customers free of charge. The concept of free ad-funded content is especially popular in online contexts where digital content is, to a great extent, funded by online advertising (cf. Papies, Eggers, and Wlömert 2011).

The concept of ‘free ad-funded content’ is somewhat close to the concept of ‘sponsored content’ (see previous article about Sponsored Content below), since in both cases the content is ‘sponsored’ by a commercial party. However, these concepts are not synonyms because in the case of free ad-funded content, the actual content is not initiated by the sponsoring (ad-funding) party. In case of free ad-funded content, the content is freely produced by the publishers and the purpose of the sponsoring company is to sponsor the content for consumers’ usage free of charge.

When publishers consider offering their content for free to certain distribution channels (e.g. tablet/eReading medium) and when the same content is sold in the other distribution channels (e.g. physical print magazine or newspaper), they face a trade-off between potential benefits and risks (cf. Papies, Eggers, and Wlömert 2011). According to academic literature, there are several benefits and risks related to free content distribution.

Potential benefits

- Attracting new customers: Free advertising-based content may attract new customers that would otherwise not use the product or service. Therefore, free content could create a “lift” in the overall number of consumers. (Papies, Eggers, and Wlömert 2011.)

- Fostering diffusion: Especially for new customers who may not have former empirical experience in tablet/eReading device-based magazines or newspapers, free content may be somewhat a risk-free option for them and encourage them to try the new medium platform. Since trialability (i.e. how easily a consumer can experiment the innovation before adopting it) is one of the key factors in the diffusion of any innovation (Rogers 2003), providing free content may be a critical factor in adoption and diffusion of tablet/eReading content.

Potential risks

- Cannibalization: The distribution of free content on certain channels may cannibalize the profits of other distribution channels (that operate on pay bases) (Papies, Eggers, and Wlömert 2011).

- Signaling of low quality: Consumers are likely to make inferences about the reasons behind companies offering free content; free content is often associated with inferior product quality which, in turn, may lead to lower valuation and reduced preference and attractiveness of content. This, in turn, keeps the number of adopters low. (Campbell 1999; Kamins et al. 2009.)

- Dislike of advertisements: Although the ad-funded models offer content free of charge, consumers have to “pay” for the content by exposing themselves to commercial messages. Therefore, consumers have to balance whether the utility of receiving free content is greater than the possible dislike effect in terms of advertisements. (Papies, Eggers, and Wlömert 2011.)

Next, we will go through some benchmark examples in which content is provided free of charge through an ad-funding affiliation:

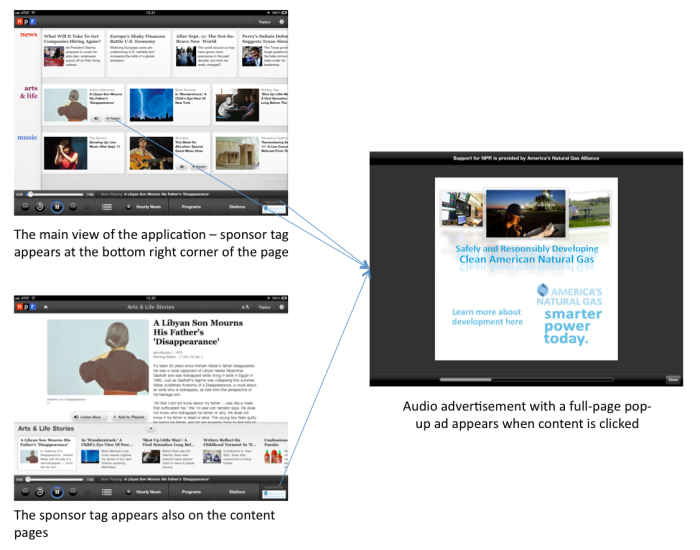

NPR, as mentioned in the previous blog post, offers audio content free of charge through a commercial sponsor affiliation. In NPR’s application, all content is free for consumers and the presence of the sponsor can be noticed both in terms of visual content (i.e. sponsor tag and pop-up ad) and auditive content (i.e. radio-like audio ads). The varying sponsor is not associated with the content itself but, rather, solely enables free content for the tablet/eReading medium. This same content, however, is also available in NPR’s website for free but there the sponsor is different.

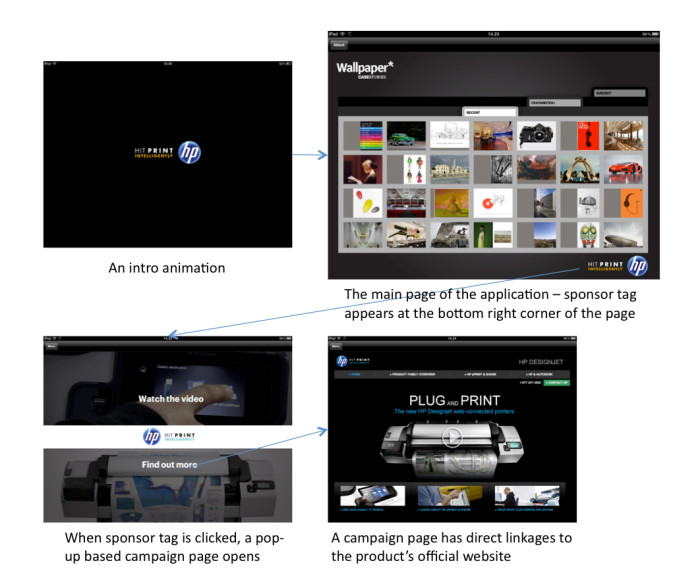

British lifestyle magazine, Wallpaper, utilizes two types of applications in tablet/eReading media; in addition to their e-magazine application, they have created a complementary application, Wallpaper Case Studies, which is built upon inspirational and entertaining photographic and video content. The magazine’s electronic application functions in a traditional way meaning that a consumer buys an issue for consumption. However, Wallpaper Case Studies operates on free ad-funded content where the high-quality and rich content is free for consumers. The presence of a commercial sponsor is done very discreetly; the presence of a commercial affiliation can be noticed only in the intro and on the main page of the application.

The idea of using multiple applications under one magazine or newspaper brand is extremely interesting in the sense that it offers a multitude of ways for utilizing advertising revenue. These revenue models do not need to be directly associated with the main product – that is, a newspaper or a magazine. For instance, a Finnish newspaper, Helsingin Sanomat, utilizes a similar solution where it not only provides readers with the actual newspaper application but also a commercially sponsored “HS.fi Kuvat” image application.

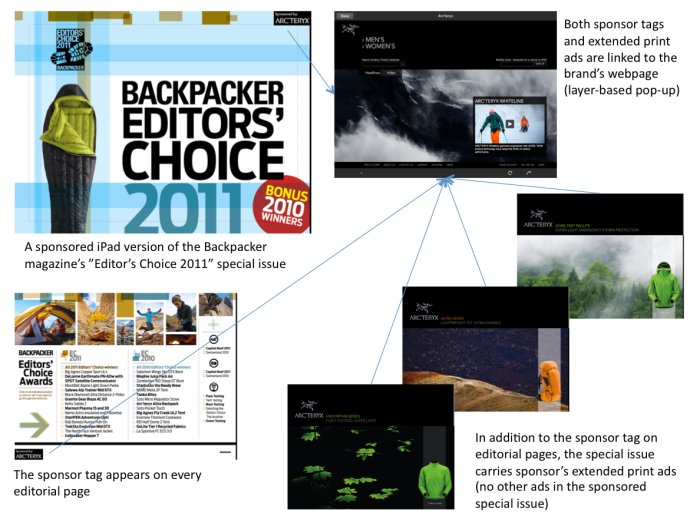

An outdoor magazine, Backpacker, offers the magazine’s special issue for free for readers whereas the normal issues of the magazine cost. In this case, ad-funding is utilized only in terms of this special issue in tablet/eReading context. As is it, exactly the same editorial content is offered in the magazine’s website without any linkages to the sponsor. Additionally, the physical version of the special issue is offered without any distinctive linkages to the particular sponsor. The Backpacker case provides a great example of how identical editorial content can be commercialized differently in different mediums. In this case, the same editorial content is provided in three places: in the physical print magazine, in magazine’s website, and in tablet/eReading context. Yet, every one of these media utilizes different advertising solutions; banners are utilized in the online environment, print advertisements in the physical magazine, and sponsorship affiliation in the tablet/eReading context.

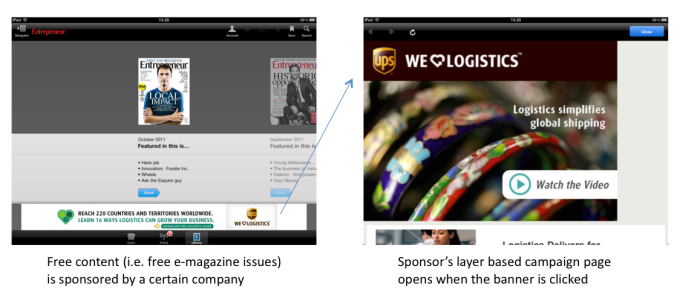

Where Backpacker magazine offers a single special issue for free for its readers, the Entrepreneur magazine offeres all issues for free through a ad-funding. Even the latest issue of the magazine, that is being sold physically nationwide, is available free of charge in the magazine’s tablet/eReading application. The sponsor affiliation is evident in the magazine application; the sponsor has a banner at the bottom of the page. In terms of Entrepreneur magazine, it is noteworthy to consider that the publisher, apparently, trusts that the free ad-funded magazines in tablet/eReading medium do not cannibalize the profits of the physical magazines that operate on a pay basis.

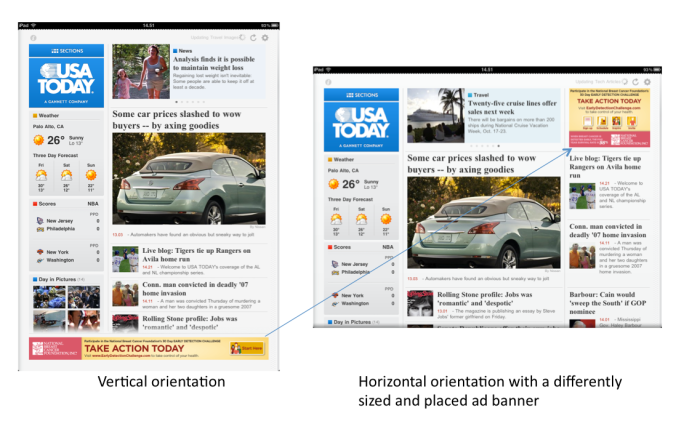

Horizontality vs. Verticality in Tablet/eReading Advertisements

Only through the development of high-resolution smart phones, it has been truly possibile that the physical attributions and moveability of medium platforms offer challenges and possibilities for the planning of advertising. As a distinct example of this, the notion of how users hold the device – either horizontally or vertically – in their hands affect the way they see the ad. In contrast to smart phones, these horizontal and vertical differences are extremely central in terms of tablet/eReading devices since these devices have been fundamentally built so that they can be used well both horizontally and vertically whereas smart phones are primarily designed for vertical use. In addition, the larger screen combined with better resolution in tablets/eReading devices provide more latitude for horizontal and vertical ad design.

The differences between horizontal and vertical orientations shall not be considered as marginal matters because several academic researches on the field of advertising have highlighted the interconnection between advertising layout and effectiveness. In their extensive eye-track study, Pieters and Wedel (2004, p. 47) found that “the brand, pictorial, and text elements of print advertisements have significant effects on attention capture”. Aribarg, Pieters, and Wedel (2010, p. 393) also found that “ad layout has direct effects on recognition memory”.

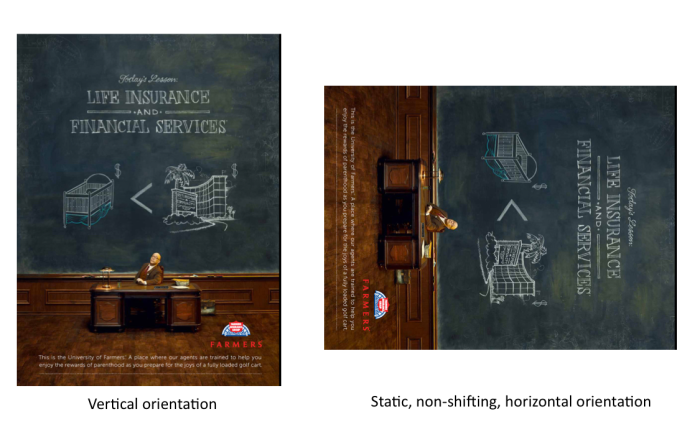

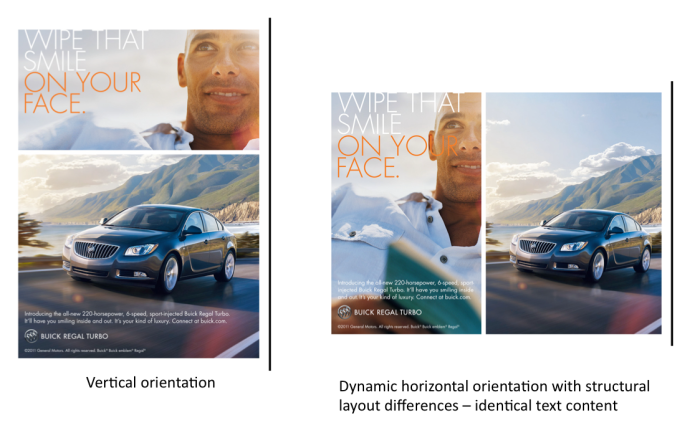

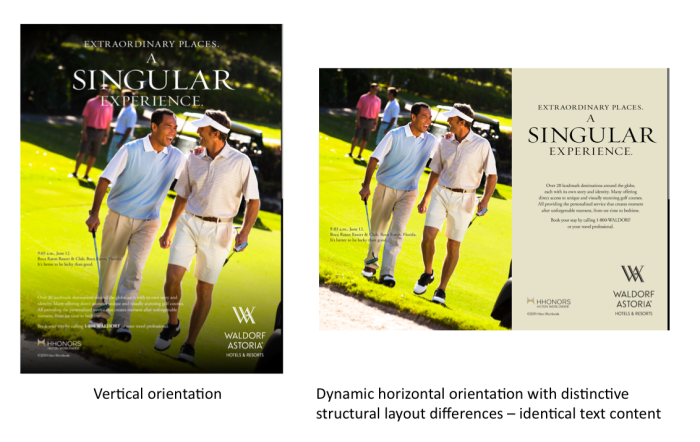

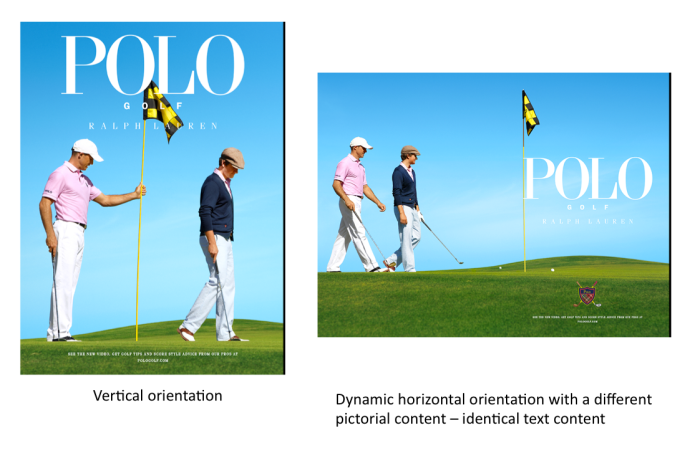

Observation within U.S. electronic newspapers and magazines indicates that verticality and horizontality play a key role in several ads; the ads are different when viewed from another angle. The following benchmark examples will highlight these differences and their extent.

At the most basic level, vertical and horizontal orientations do not affect the way the an ad is perceived. In other words, an ad is “locked” to a certain position/orientation meaning that the ad does not change depending on the viewing angle. These kinds of solutions are often prominent is newspaper and magazine applications where the entire application is locked to a particular position/orientation and does not, as a whole, support other viewing angles.

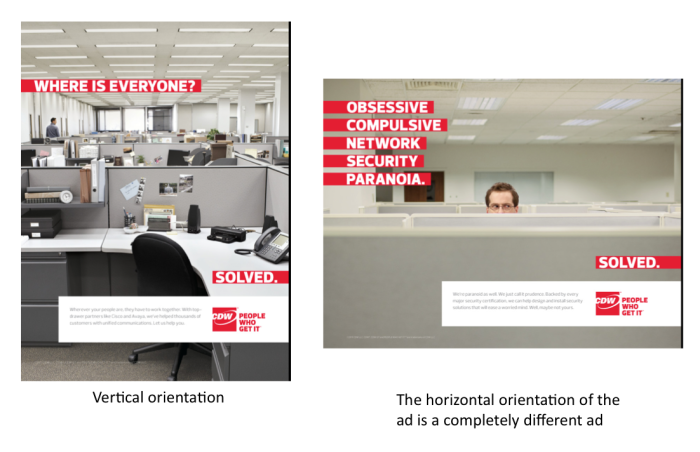

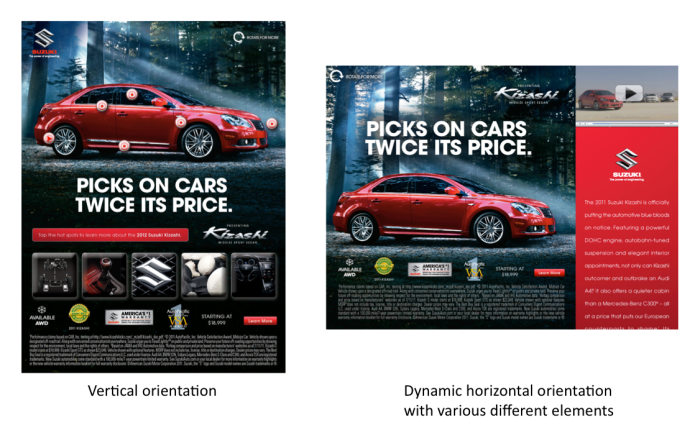

Figures 39 and 40 demonstrate simple shifting between horizontal and vertical orientations. In both examples, the text content is static, but the visual elements and the composition of the ad are different depending on the viewing angle. Figure 40 illustrates more distinctive layout differences between these orientations.

Figure 41 and 42 point out the idea of using different pictorial content in vertical and horizontal ad versions. In Figure 41, the ad is merely built upon non-informative brand image pictures and the changes in orientation do not produce remarkable pictorial differences. Respectively, Figure 42 utilizes informative product-centered photos and, therefore, displays the pictorial content distinctively diversely. In addition to the pictorial differences, the color schemes are different in vertical and horizontal orientations.

Figure 43 also utilizes different pictorial content in different orientations. In addition, the text content is different and, thus, the whole meaning of the ad changes when orientation changes. This is a great example of how the same advertising space can be utilized in a dualistic manner.

Figure 44 illustrates how different orientations have different content and functionalities. The vertical version contains touchable hotspots whereas the horizontal version utilizes video content.

Figure 45 demonstrates how the other orientation can be used as a “teaser” for the ad. In this case, the horizontal version does not provide any advertising-focused content and the purpose of the page remains somewhat unclear for the reader. When the orientation is shifted, however, the actual advertisement with functionalities is revealed.

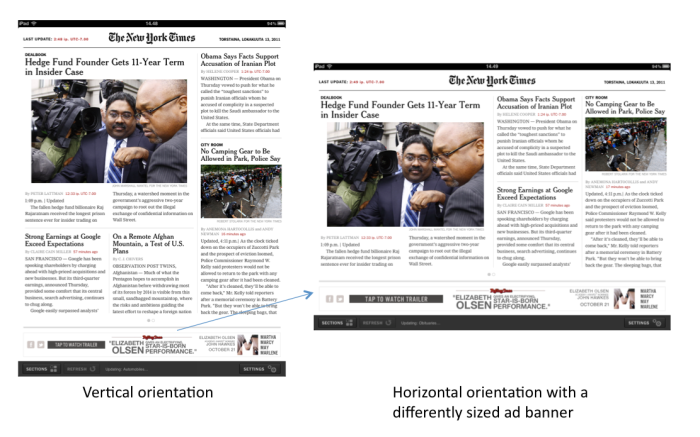

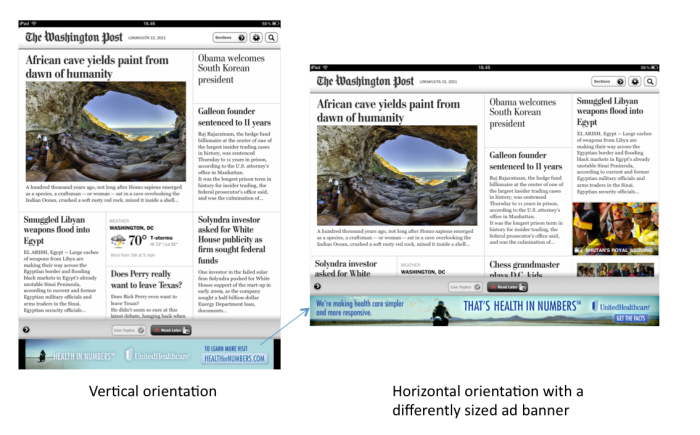

Figures 46, 47, and 48 show that the orientation differences do not only affect full-page advertisements but also have implications for banner advertising in newspaper applications. The size, shape, and composition of banners change when the viewing angle is changed.

The Potential of Sponsored Content in Tablet/eReading Context

Originating from radio and television (Harvey, Gray, and Despain 2006), sponsored content advertising refers to commercial message that has been embedded into relevant, non-commercial context (cf. Advertising on the Internet: Implications for Marketers and Advertisers 1997). In online environment, sponsored content is especially popular among informational websites, where sponsored content aims at offering useful information to consumers and, hence, offers companies a way to become part of the community (Becker-Olsen 2003). Since tablet/eReading medium is inherently built around informational content sharing, sponsored content may offer new kinds of commercial possibilities for magazines and newspapers.

In terms of any media, sponsored content can be seen as a lucrative investment in an activity, cause, or event in order to access commercial potential (Meenaghan 1983) – that is, increase or enhance brand awareness (Cornwell, Ray, and Steinhard 2001; Gwinner 1997; Johar and Phani 1999; Stipp 1998), and corporate or brand image (Cornwell, Ray, and Steinhard 2001; Gwinner 1997). In its most efficient form, it is possible to talk about “true sponsorship” that is characterized by exclusivity/visibility of information and emotive connection to consumers (Harvey, Gray, and Despain 2006).

Sponsoring is often confused with traditional banner advertising. However, sponsored content is different from banner advertising which is used mainly on pages that operate on membership revenue (Becker-Olsen 2003) and introduce promotional inducements in order to create higher levels of involvement and processing (Krishnamurthy 2000; Sparta 2000) and boost click-through rates (Becker-Olsen 2003). Despite the related benefits of banner advertising, it appears that this form of advertising is losing its effectiveness as click-through rates have declines substantially in the past few years (Snyder 2001) and sponsorship revenues seem to be cumulating faster than banner revenues (Harvey, Gray, and Despain 2006).

Sponsored content entails three typical characteristics. Let us go through these central elements in more detail:

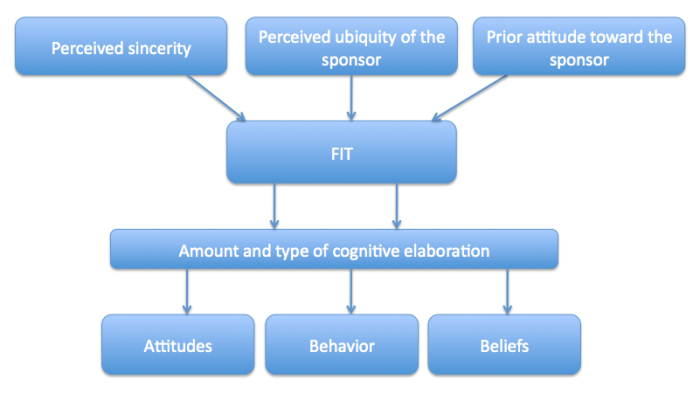

1. Role of fit

Fit is a central component in sponsoring. Herein, fit refers to the extent how compatible sponsoring is with the audience. If companies have low-fit programs, the programs generate more thoughts in consumers’ minds and, consequently, may lead to negative experiences (Madrigal 2000). On the contrary, fit has an impact on consumer interest in the sense that if interest increases, so will purchase intentions (Becker-Olsen 2003). Figure 1 shows the structure and role of fit in terms of sponsored content. The figure points out how perceived sincerity of the sponsor, perceived ubiquity of the sponsor and prior attitudes toward the sponsor affect perceived fit of sponsoring which, in turn, has an impact on how much and what kind of cognitive processing consumers do. This, ultimately, leads to formation of consumer attitudes, behavior, and beliefs. (Speed and Thompson 2000; Becker-Olsen and Simmons 2002; Becker-Olsen 2003.) Fundamentally, if the program is high-fit, consumer attitudes, behavior, and beliefs toward the program will, most likely, be positively influenced.

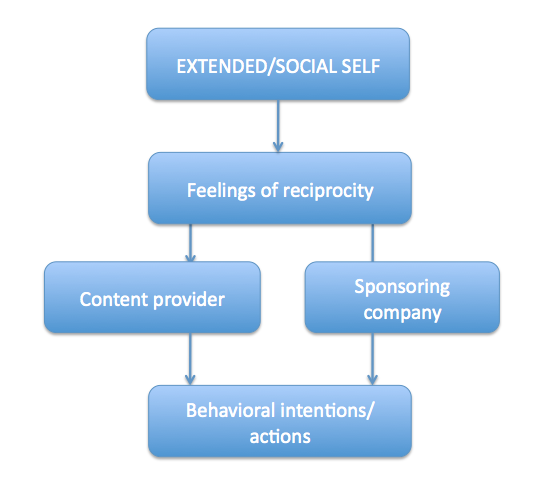

2. Role of social identification and reciprocity

Social identification and reciprocity affect how sponsoring is perceived by consumers. In case of sponsored content, it is important to notice that the extent and amount of membership affinity has an impact on the feelings of reciprocity (Becker-Olsen 2003). Figure 2 highlights the role of extended or social self in sponsoring. In particular, consumers’ feelings of reciprocity depend on how engaged they are in the community – if they are committed on a personal level to the company (i.e. have a strong positive relationship with the firm), they will feel good about the provided information and have sense of responsibility for the success or failure of the content provider or sponsoring company. This, in turn, affects consumers’ behavioral intentions and actions as the probability of purchase intentions increases. (Becker-Olsen 2003.)

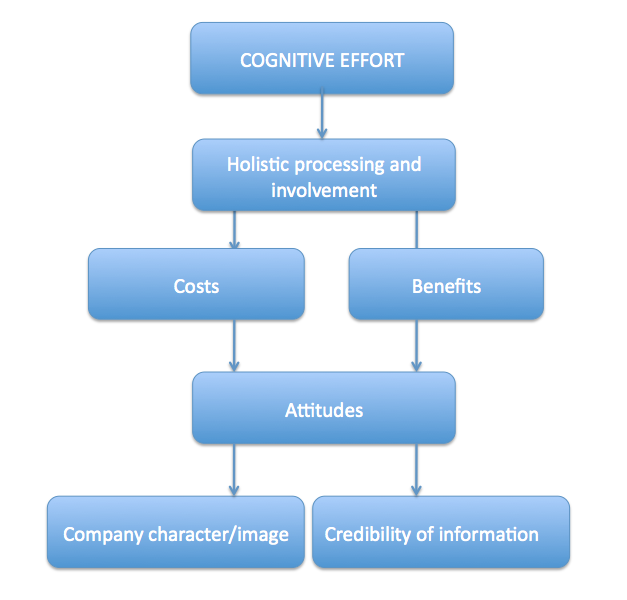

3. Role of cognitive effort

Cognitive effort is also an essential component of sponsored content. As it is, sponsored content may cause higher levels of processing and involvement in consumers (i.e. produce greater and more holistic cognitive elaboration) than simple product-centered banner or print advertising. Cognitive effort is both detrimental and beneficial as it causes additional ”costs” (i.e. consumers question sponsor’s motive, trust, expertise, and editorial control) but entails, on the other hand, also great “benefits” (i.e. increased learning and positive affect for consumers). (Becker-Olsen 2003.) These costs and benefits together determine the type of attitudes consumers develop towards the company behind the sponsorship affiliation – that is, how they think about the company in general (i.e. image and character) and how trustworthy they perceive the supplied information (i.e. credibility). (Becker-Olsen 2003; Fiske and Taylor 1984; Clarbaniio and Edell 1997; Isen and Means 1 9S3; Payne 1982.) Figure 3 demonstrates the structure of cognitive effort and its role in sponsored content.

Benefits

Sponsoring entails several benefits both for the publisher and the sponsor. Sponsorship has a positive impact on consumers’ feelings of gratitude, affinity, and overall satisfaction. Additionally, sponsoring allows companies to overcome many of the obstacles involved in banner advertising (e.g. too product-centered elaboration). Secondly, sponsoring enhances consumers’ perception and image of the brand and develops positive attitudes toward the sponsor. Thirdly, sponsored content has an impact on consumers’ self-consistency minimizing, thus, associated cognitive dissonance. Sponsoring, furthermore, impacts responsiveness positively in the sense that the sponsor is perceived as being more responsive to consumer needs and consumers may behave more responsively towards sponsored content. Also, consumer beliefs are influenced positively (i.e. consumers’ feelings of sponsor’s expertise, credibility, and trust are enhanced), and the overall perceptions of sponsor’s status (i.e. category leadership) and assortment (i.e. product quality) are improved. It has additionally been noted that consumers tend to recall sponsored content better than other content and sponsoring helps in building strong, lasting customer relationships. Finally, sponsoring is to eventually improve company sales and have a positive effect on the return on investment in advertising. (Beckwith and Lehmann, 1975; Harvey, Gray, and Despain 2006; Next Century Media 2000, 2005; Hooper 1968; Norman Hecht Research Studies 1990; Logan 2000; Mara 2000; Advertising on the Internet: Implications for Marketers and Advertisers 1997; Pack 2011; Becker-Olsen 2003.)

Implications for tablet/eReading context

Despite the notion that sponsored content is a highly relevant concept in tablet/eReading medium, sponsoring has been utilized only to a small extent as an advertising form in tablets and eReading devices. However, one can assume that the utilization of this form of advertising will dramatically increase in near future. Advertisers and publishers may consider planning and implementing sponsored content according to the following guidelines. First of all, sponsored content needs to stand out from most programs (i.e. it needs to be ”special”). Secondly, sponsored content should aim at providing useful information and delighting consumers with a positive surprise (e.g. offering information about undiscovered and novel subjects). Thirdly, publishers need to make sure that the sponsored content is highly visible and transparent. This means stating clearly what is advertising and what is editorial content so that consumers do not get confused. Fourth, it is suggested that advertisers move away from impressions-based brand planning towards true “engagement”. This means focusing efforts on getting consumers to stay with the brand’s messaging and encouraging emotional bonding with the brand. Finally, sponsored content may be combined with banner advertising resulting in integrated campaigns. This requires attending that the program is well targeted and highly relevant for the audience. (Becker-Olsen 2003; Harvey, Gray, Despain 2006.)

Advertising Types in eReading/Tablet Context – Embedded Campaign Sites

Embedded campaign sites in the tablet/eReading context are website-like advertisements that are created around certain products or services. They differ in content and functionalities. Where static print advertisements in tablets/eReading devices are mainly electronic copies of physical magazine print advertisements, embedded campaign sites, in turn, are whole advertising sites embedded into electronic magazines and newspapers. Yet, inside these ads there are different advertising elements that are common both in print and online advertising. These elements include, for instance:

- Texts: Text sections utilize both advertising-like copywriting texts and product- or service-specific information texts. Often it is exactly the copywrite text that aims at catching the reader’s attention on the front page of the ad; product or service specific information is usually placed in sub-sites in the ad that open on top of the page from the main page’s menu.

- Photos: It is possible to utilize various options with regard to images. Especially, these options are useful with regard to embedded campaign sites where the size of the ad is not static but, rather, builds on sub-sites. In addition to front page images, it is possible to add product catalogs (Figure 34) or different brand image photos (Figure 32) to the sites.

- Videos: Videos may be commercials or demonstrations where product or service characteristics are being explored through animated images and sound.

- Touchable Content: Embedded campaign sites have been also utilizing touchable screens of devices by offering a 360 degree product images (Figure 35). Instead of letting readers click the images in a traditional manner, the sites have enabled a more creative way of “twiddling” the product.

- Social Media Linking: Several embedded campaign sites have been utilizing social media in a distinct way. Often this means linkages to company’s or brand’s Facebook or Twitter page (Figures 32, 33, 34, 36). It appears that linkages to social media platforms are created mainly to get readers to become followers for the company or brand in diverse media. In some cases, it is also possible to share ads or content to other social media platforms via specific social media sharing tools (Figure 36).

- User-Generated-Content: Users can leave comments to embedded campaign sites. For instance, a user can take part in discussions within advertising pages and, hence, interact with other users (Figure 37).

- E-Commerce: The tablet/eReading medium has enabled a clear innovation in advertising; purchasing inside magazine ads. It seems that U.S. advertisers have been knowledgeable about the potential of e-commerce inside tablet media and, thus, taken advantage of it by offering readers with the purchasing option of products (see Figures 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37). Very often company’s own e-shop opens on top of an ad enabling a more user-friendly way of interacting with the offering. It is also possible to close this layer conveniently with a single click. On the other hand, it is also possible that readers are being automatically directed to an e-shop based on a single click. Herein, readers leave the magazine application and need to manually navigate back to the magazine after having browsed the e-shop.

- Lead Generation: When it comes to more complex products (such as cars) or services (such as customized professional services), embedded e-commerce logic is not utilized but, rather, companies take advantage of “call-to-action” in lead generation. In terms of readers, this means submitting one’s contact information so that representatives of the advertising company may contact the reader in future.

Embedded campaign sites are being implemented in two ways: 1) either there’s a full-page advertisement (i.e. embedded campaign site) between editorial pages that the reader comes across while browsing the magazine, or 2) there is an ad banner among editorial content via which the layer-based campaign site opens.

In the following chapter, some benchmark examples of embedded campaign sites in tablet/eReading medium context are presented:

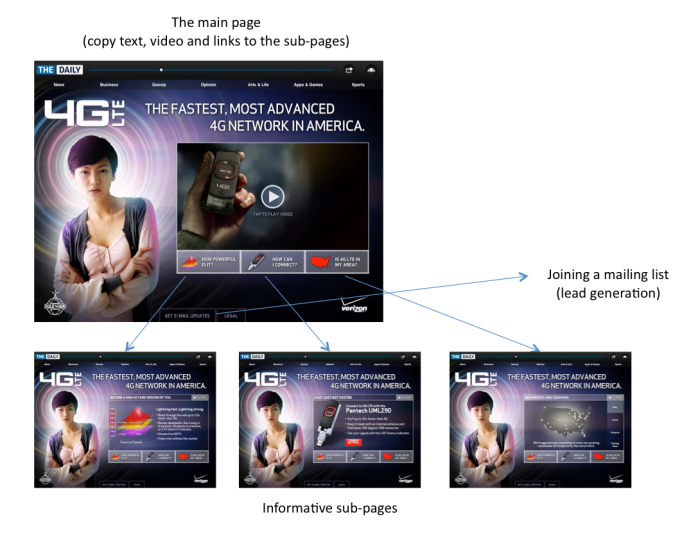

The Verizon ad (Figure 31) in The Daily magazine entails a front page and three sub-pages. The main page includes an embedded commercial video whereas sub-pages offer additional information about the product’s technical characteristics. This whole page ad has been placed between editorial pages.

The Sperry ad (Figure 32) in Elle magazine resembles traditional print ad but entails web functionalities. For instance, right in the front page there’s a scrollable photo gallery. Additionally, the page has distinct clickable links to the brand’s e-shop and social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter).

Another Verizon ad (Figure 33), in turn, entails many of the same elements as the former one (see Figure 31). This ad highlights purchasing option to a great extent both in main page and sub-pages. There’s also a linkage to the company’s Facebook page.

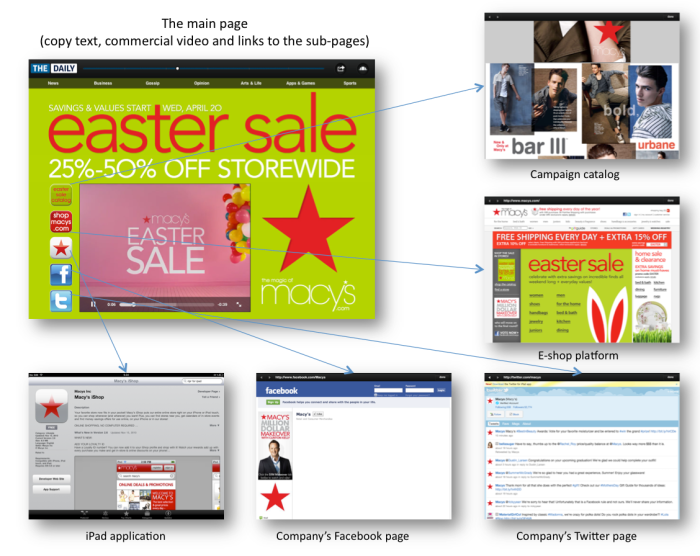

The Macy’s ad in The Daily magazine utilizes in its embedded campaign site various functionalities: video, up-to-date online product catalog, social media, e-shop, and linkage to iTunes, through which readers can download the company’s mobile application.

The Verizon mobile phone ad (Figure 35), in turn, applies a scrollable 360 degree image technique. When a reader turns the product around, the ad communicates back to the reader with additional information about the product. Thus, a reader gets different information depending on the angle from which the product is watched. Also, the product can be purchased through the company’s e-shop that opens on top of the page.

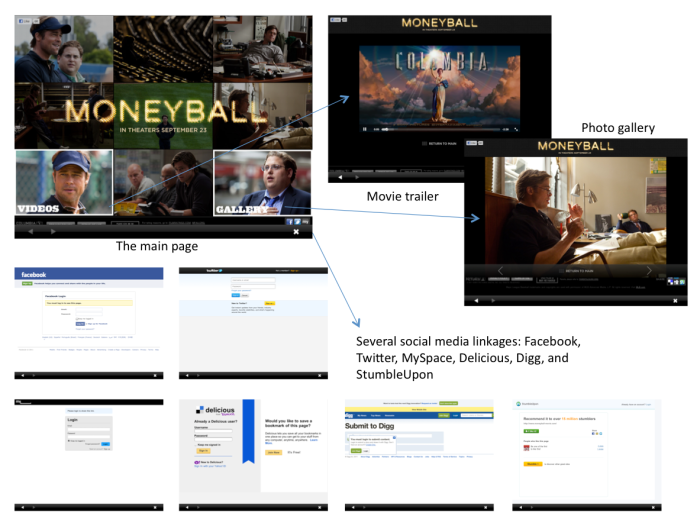

In an advertising page for Moneyball movie (Figure 36) offers people with the option of watching a trailer from the film and browsing an image gallery. Also, the page takes advantage of social media sharing tools to a great extent.

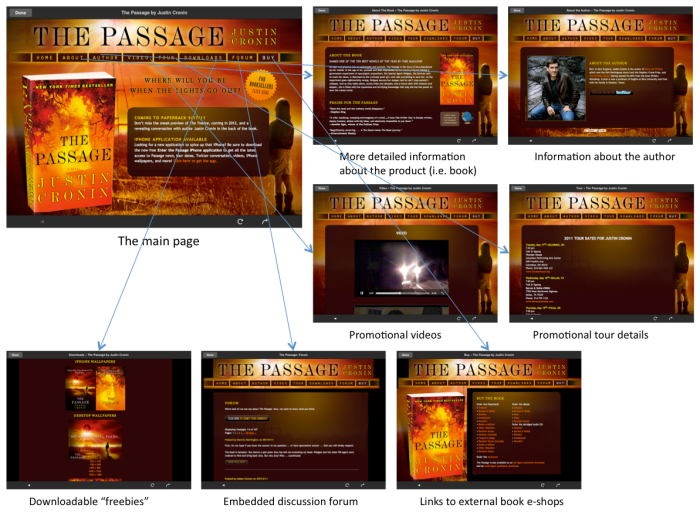

The embedded campaign site for a novel book, The Passage (Figure 37), has been customized for tablet/eReading devices. It resembles the book’s official website greatly (actually, seems to be an identical version of it) and, thus, offers various online functionalities. This ad has been seamlessly embedded between the editorial pages in the newspaper.

The Potential of Location-based Advertising in Tablet/eReading Context

Location-based advertising (LBA) in an online context is an under-researched area and has only recently become the interest of academics due to its major potential (cf. Bruner II and Kumar 2007; Unni and Harmon 2007). LBA is a new tool for marketers (Unni and Harmon 2007) for interacting with consumers in new and innovative (Kenny and Marshall 2000) customer-centric one-on-one ways (Seth, Sisodia and Sharma 2000; Watson et al. 2000). Since most eReading devices – especially multifunctional tablets, such as iPad, Galaxy Tab and Nook Color – include GPS capabilities, LBA entails a tremendous potential for eReading/Tablet-based advertising.

The modern network era enables individual interactions with consumers at any given time and place (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Yet, the personal nature of online devices (James 2000; Unni and Harmon 2007) leads to location paradox where consumers wish to remain anonymous while being exposed to LBA (Rimkus 2000). A major risk, thus, exists for LBA to be perceived as intrusive (Banerjee and Dholakia 2008) spamming (Fuller 2005), the sending of unsolicited messages, as consumer attitudes towards LBA are generally slightly negative (Bruner II and Kumar 2007), privacy concerns are high and perceived benefits and value of LBA are low (Unni and Harmon 2007). However, especially local brick-and-mortar retailers, competitors and complementary businesses (e.g. vending machines) may benefit from LBA (Bruner II and Kumar 2007).

In a traditional context, LBA has been referred to as marketer-controlled marketing information specifically tailored via location-tracking technology for the place where users access an advertising medium (Bruner II and Kumar 2007; Unni and Harmon 2007). Increasingly, due to advances in information technology (e.g. automatic generation and update of location data) (Unni and Harmon 2007), LBA becomes real-time marketing (Oliver, Rust, and Varki 1998) of personalized location-specific products and services (Unni and Harmon 2007) thus removing geographical and information barriers (Banerjee and Dholakia 2008).

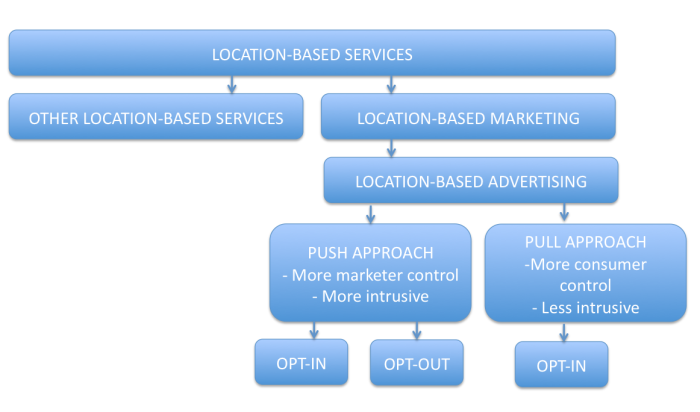

LBA can be seen as a form of telematics (Clements 2004) where location-based marketing (LBM) or location-based services (LBS) (Driscoll 2001; Küpper 2005), with the potential of increasing customer value (Jagoe 2003), can be accessed through personal vehicles via GPS, Bluetooth or RFID (Bruner II and Kumar 2007) by ultimate consumers (e.g., Kölmel and Alexakis 2002). LBA involves push and pull strategies (Paavilainen 2002) that differ in the type of promotion and aimed target (e.g., Shimp 2003, 472). Push strategies involve advertiser-initiated location-based promotion in the form of opt-in / permission marketing (user-authorized promotion) or generally illegal opt-out (random targeting) whereas pull strategies involve consumer-initiated information seeking and consequent exposure to location-based promotion (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Opt-in LBA seems to be more effective (Unni and Harmon 2007) due to ensured precision in permission marketing or targeting (Godin 1999).

LBA messages may be brand-building ads, special offers, and different types of promotions (Barwise and Strong 2002). Opt-in LBA’s infotainment content is perceived positively whereas irritation is perceived negatively. Particularly, unlike utilitarian LBS, LBA supposedly needs to be free for customers (Unni and Harmon 2007).

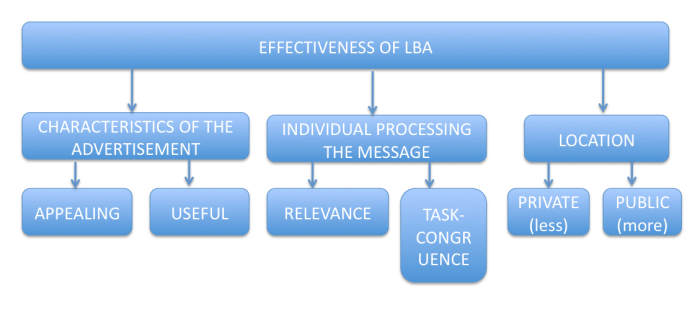

The effectiveness of LBA depends on several factors, such as:

When benefits, such as personalized messages (Kalakota and Robinson 2002), time saving (Ho and Kwok 2003), right time and place (Kenny and Marshall 2002), feeling of exclusivity (Simonson 2005) exceed associated non-monetary costs of time, effort and psychological costs (Baker et al. 2002) together with monetary costs, customers are willing to be exposed to LBA (see e.g. Goodwin 1991; Olivero and Lunt 2004).

In general, in order to maximize the benefits of LBA, crippling laws need to be avoided and national opt-in and opt-out databases may be developed (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Marketers, trusted service providers in particular, face a major challenge in offering LBA as an interesting, beneficial (i.e. value proposition), and safe (i.e. privacy controlled) option for customers. Consequently, LBA may be offered in the vicinity of certain retail locations and malls or, alternatively, incentives, such as reduced service rates or no charge, may be offered. Number of pull LBA requests could also be linked to reward programs and other services may be bundled with LBA. Furthermore, while pull approach is to be favored, push opt-in promotional marketing (not advertising) may be used for triggering impulse buying. (Unni and Harmon 2007.)

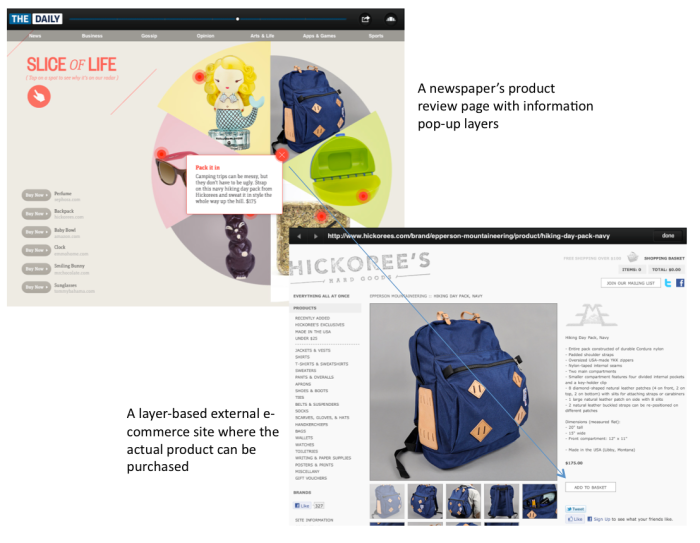

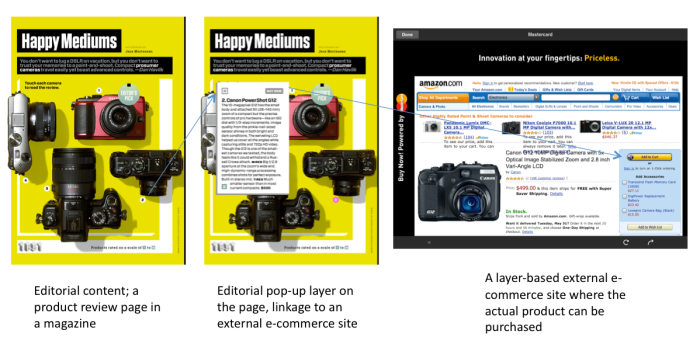

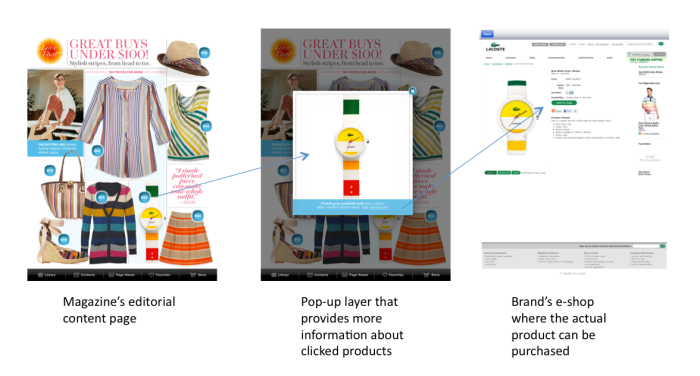

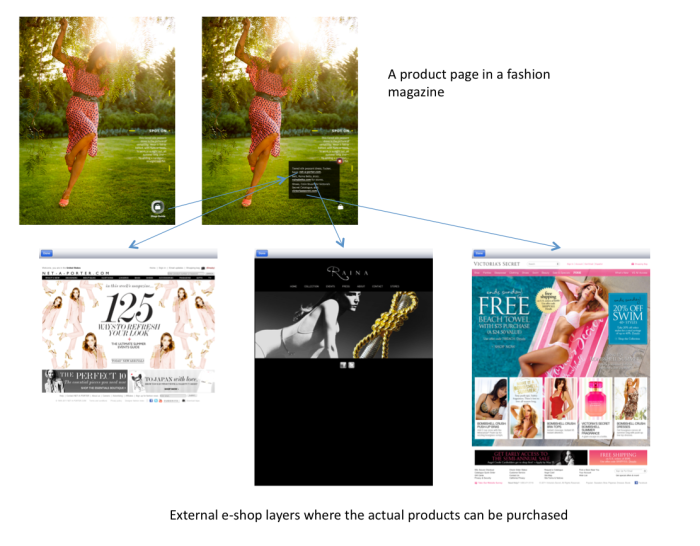

Advertising Types in eReading/Tablet Context – Functional & Commercially-Orientated Content

The product review pages of newspapers and magazines, such as outlooks on fashion, are a clear sign of how direct e-commerce may be embedded into independent editorial content. In terms of tablets and some eReading devices, the advanced technological characteristics enable that it is possible to seamlessly move away from non-commercial, unbiased editorial content to a commercial e-commerce environment. However, this kind of novel phenomenon is not to be confused with the concept of ‘advertorials‘ where advertisers consciously aim at creating content that resembles editorial content and that consumers might, by mistake, regard as being non-commercial content which, in turn, might lead to a much more positive attitude towards the advertised product(s). Indeed, advertorials are created by advertisers and commercial content is, by contrast, part of editorial content with direct e-commerce linkages. From readers’ point of view the straight linkage to commercial platforms is reasonable since direct linkages save consumers time and effort in purchasing. In particular, layer-based e-shops, that open on top of a page, bring additional value to consumers as they often offer richer information about products and services. Hence, readers do not need to close an open newspaper or magazine application and open a web browser but, instead, they get the information immediately.

Despite this distinct additional value, it is central to consider ethical issues. Especially, it is noteworthy to consider the point when the unbiased, editorial content turns into commercial announcements. This kind of content does not serve the reader but, rather, generates sales through editorial content. As it is, commercial content in eReading and tablet media resembles to a great extent the concept of affiliate marketing where publishing parties direct consumers to merchants’ environment (that is, e-commerce platforms) and receive commissions on every actualized act, such as site visits or realized sales. In an online context, these affiliate publishers are often individual actors, such as bloggers, whose actions are not under such harsh scrutiny; their operations are not regulated in a similar manner in terms of commercial and editorial content.

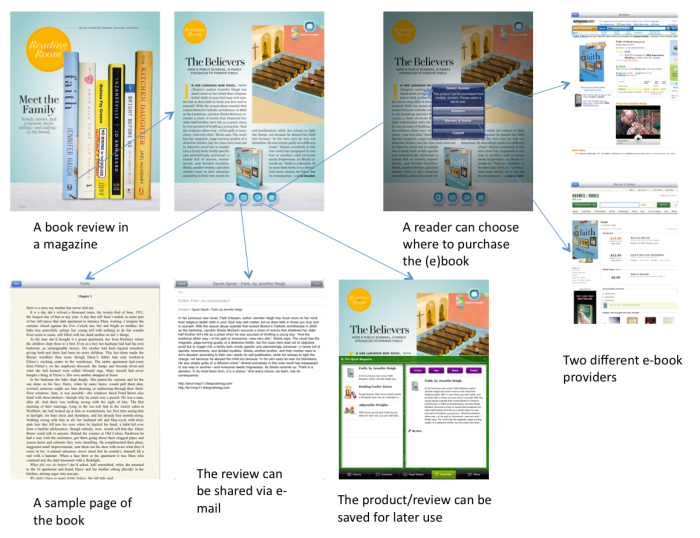

In terms of U.S. magazines and newspapers, both editorial content and e-commerce have been utilized in a multifaceted way when it comes to consumer products. Let’s go through some benchmark examples:

For instance, The Daily newspaper (Figure 25) has its own product display page, ‘Slice of Life’, where diverse consumer products are presented shortly. Each product can be purchased via an e-shop layer that opens on top the page.

Secondly, women’s fashion magazine, Elle (Figure 26), presents cosmetics by directing readers to an e-shop. A similar pop-up layer technique is utilized in Elle.

Thirdly, Wired magazine (Figure 27) presents consumer products in a very sales-oriented manner. Differing from various other newspapers and magazines, Wired announces in its product review page (a small vertical text on the bottom right) that “WIRED receives a commission on sales.” In this sense, we are clearly dealing with an online affiliate site where editorial content does not only serve the reader but also the magazine itself; it is part of the e-magazine’s revenue model.

Fourth, The Oprah magazine (Figure 28) enables web-based shopping through a magazine-like layout. In this magazine, a product-specific pop-up window opens on top of the page enabling consumers to access products’ own e-shops.

In addition, The Oprah magazine (Figure 29) displays women’s fashion stylishly through images. Herein, it is not possible to purchase products directly but, rather, via “Shop Guide” navigation bar. Also The Oprah magazine utilizes pop-up layer technique by opening the e-shop layers on top of pages.

The Oprah magazine (Figure 30) has greatly utilized e-commercialism when it comes to book reviews. In terms of actual purchasing, the magazine offers consumers with the option of choosing whether they want to order a physical or an electronic product via Amazon.com or Barnesandnobles.com. Besides having enabled e-commerce, the magazine offers consumers with the possibility of reading an example page of a book, sending a review via e-mail to a friend, and saving the product for a later, eased access. These kinds of additional services are widely used in more traditional e-shops and it is interesting to see the extent to which online magazines and newspapers adopt e-shop-related characteristics in their own applications.