The Potential of Location-based Advertising in Tablet/eReading Context

Location-based advertising (LBA) in an online context is an under-researched area and has only recently become the interest of academics due to its major potential (cf. Bruner II and Kumar 2007; Unni and Harmon 2007). LBA is a new tool for marketers (Unni and Harmon 2007) for interacting with consumers in new and innovative (Kenny and Marshall 2000) customer-centric one-on-one ways (Seth, Sisodia and Sharma 2000; Watson et al. 2000). Since most eReading devices – especially multifunctional tablets, such as iPad, Galaxy Tab and Nook Color – include GPS capabilities, LBA entails a tremendous potential for eReading/Tablet-based advertising.

The modern network era enables individual interactions with consumers at any given time and place (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Yet, the personal nature of online devices (James 2000; Unni and Harmon 2007) leads to location paradox where consumers wish to remain anonymous while being exposed to LBA (Rimkus 2000). A major risk, thus, exists for LBA to be perceived as intrusive (Banerjee and Dholakia 2008) spamming (Fuller 2005), the sending of unsolicited messages, as consumer attitudes towards LBA are generally slightly negative (Bruner II and Kumar 2007), privacy concerns are high and perceived benefits and value of LBA are low (Unni and Harmon 2007). However, especially local brick-and-mortar retailers, competitors and complementary businesses (e.g. vending machines) may benefit from LBA (Bruner II and Kumar 2007).

In a traditional context, LBA has been referred to as marketer-controlled marketing information specifically tailored via location-tracking technology for the place where users access an advertising medium (Bruner II and Kumar 2007; Unni and Harmon 2007). Increasingly, due to advances in information technology (e.g. automatic generation and update of location data) (Unni and Harmon 2007), LBA becomes real-time marketing (Oliver, Rust, and Varki 1998) of personalized location-specific products and services (Unni and Harmon 2007) thus removing geographical and information barriers (Banerjee and Dholakia 2008).

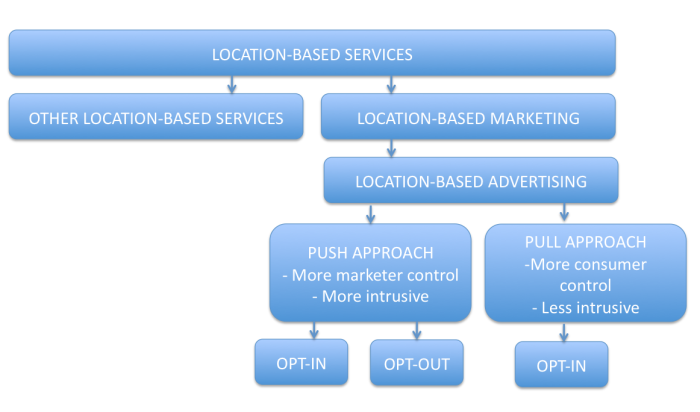

LBA can be seen as a form of telematics (Clements 2004) where location-based marketing (LBM) or location-based services (LBS) (Driscoll 2001; Küpper 2005), with the potential of increasing customer value (Jagoe 2003), can be accessed through personal vehicles via GPS, Bluetooth or RFID (Bruner II and Kumar 2007) by ultimate consumers (e.g., Kölmel and Alexakis 2002). LBA involves push and pull strategies (Paavilainen 2002) that differ in the type of promotion and aimed target (e.g., Shimp 2003, 472). Push strategies involve advertiser-initiated location-based promotion in the form of opt-in / permission marketing (user-authorized promotion) or generally illegal opt-out (random targeting) whereas pull strategies involve consumer-initiated information seeking and consequent exposure to location-based promotion (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Opt-in LBA seems to be more effective (Unni and Harmon 2007) due to ensured precision in permission marketing or targeting (Godin 1999).

LBA messages may be brand-building ads, special offers, and different types of promotions (Barwise and Strong 2002). Opt-in LBA’s infotainment content is perceived positively whereas irritation is perceived negatively. Particularly, unlike utilitarian LBS, LBA supposedly needs to be free for customers (Unni and Harmon 2007).

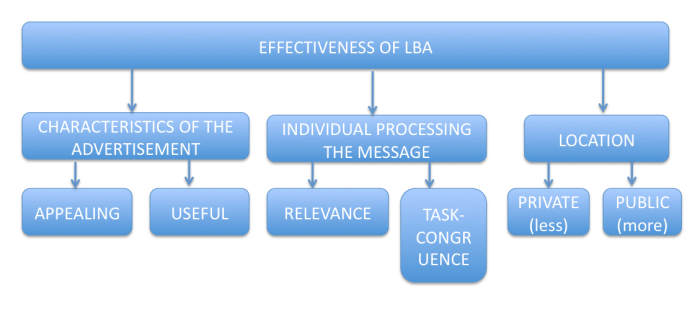

The effectiveness of LBA depends on several factors, such as:

When benefits, such as personalized messages (Kalakota and Robinson 2002), time saving (Ho and Kwok 2003), right time and place (Kenny and Marshall 2002), feeling of exclusivity (Simonson 2005) exceed associated non-monetary costs of time, effort and psychological costs (Baker et al. 2002) together with monetary costs, customers are willing to be exposed to LBA (see e.g. Goodwin 1991; Olivero and Lunt 2004).

In general, in order to maximize the benefits of LBA, crippling laws need to be avoided and national opt-in and opt-out databases may be developed (Bruner II and Kumar 2007). Marketers, trusted service providers in particular, face a major challenge in offering LBA as an interesting, beneficial (i.e. value proposition), and safe (i.e. privacy controlled) option for customers. Consequently, LBA may be offered in the vicinity of certain retail locations and malls or, alternatively, incentives, such as reduced service rates or no charge, may be offered. Number of pull LBA requests could also be linked to reward programs and other services may be bundled with LBA. Furthermore, while pull approach is to be favored, push opt-in promotional marketing (not advertising) may be used for triggering impulse buying. (Unni and Harmon 2007.)

Leave a comment